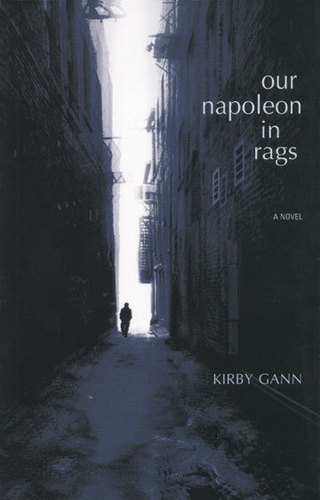

Our Napoleon in Rags

Better and nimbler than the hand is the thought which wrought through it.

Can one man change the world? Haycraft Keebler, self-appointed savior of humanity, believes his mission is to inspire the people to rise up against the powers that be. And he will use any idea that springs from his bipolar mind – distributing a “revolutionary” newsletter, covering debris and trashcans in gold, instigating a bus crash – to achieve his goal of social equality for all.

Most of Haycraft’s schemes and dreams are hatched at the Don Quixote, a neighborhood bar founded on unlikely principles. The regulars there – an errant cast of society’s dispossessed – keep a watchful eye over their well-meaning, but mentally unstable “Napoleon in Rags.” The bonds that hold together this fragile group of outsiders are forever changed, however, when Haycraft falls in love with a fifteen-year-old male street hustler. Weaving the hot button issues of mental illness, homosexuality, police violence, and racism through a novel that is nearly Victorian in its graceful storytelling, Kirby Gann has created not only an extraordinary read, but a scathing commentary on contemporary America.

From the Novel:

TRAILING WINDMILL SAILS

The nights at the Don Quixote – that sumptuous dive – held darker than nights elsewhere, even if the club sat huddled within the smacked heart of the city. As in the rest of America (and for most Americans), this heart rarely became an object of attention and care, more fretted over than attended to, arteries hardening without complaint, a condition forming without the host’s knowledge. Like the biological heart, one remained aware but avoided the subject. One leaves the heart alone and hopes for the best.

We are in Old Towne, the broken-streetlight district in Montreux where dark house-stoops offer no welcome. Most of the light that sparked through the leaded wave windows of the Don Q was of the flashing variety, red and blue and sometimes white – vascular colors. The regulars called the Don Q the heart of Old Towne, thus making it the heart within the heart.

The original, stately farmhouse had once sat well outside city limits in 1865. As the decades passed it suffered add-ons and reconstruction to the point of invisibility, subsumed by brick. In our own time, the Don Quixote fell victim to the Come Back to Montreux! campaign, that brief resuscitation effort sponsored by the city council in the 1980s. They slashed mortgage rates in the vain effort to stave urban sprawl, inviting the wealthy to reinvest in squalid mansions left over from a more elegant era. Everyone believed Old Towne should have been the crown jewel to the city, a Dresden captured in amber glass on the muddy Ohio bank to lure tourists up from the Charleston and Savannah wastelands. But that support was arrested by a number of awful events, acts between the poor and dissolute confronted by the moneyed’s sudden interest, a history better left to sociologists studying the consequences of strikes, assaults, rapes, and murder. The campaign restored a few strewn blocks of eclectic architecture, but most of the homes remained arsoned-empty, or skinned by molding scaffolding, the hides of plastic sheets. What was left were hookers of all specialties and interests; adult bookstores barking private video booths; men in raincoats skipping over splashed glass in the streets, headed for the pawnshop brokers and liquor stores protected by pig-iron bars. And the Don Quixote, ferned and atriumed toward the glittering stars.

A wicket gate and garden path led to the entrance, crowned by a ragged windmill that was useless but for effect. Inside, the tiled floor swept down five quick stairs onto a mahogany and teak sunken bar. Above, in the original farmhouse, stretched the Theatre Room, where unsung playwrights presented works-in-progress, poets of the rant school sieged the stage for endless hours, and bands of every style played deep into the night. Though somewhat devout Christians, Beau and Glenda Stiles (the owners) still harbored bits of Bohemian soul.

Near the sunken bar there, under corroded lattice-work and paper lamps put up for sale by a Third World economic savior organization, Haycraft Keebler parlayed his days. As did Glenda and Beau, with their hapless helpmeet Mather Williams; as did the half-Cuban Romeo Díaz and his love Anantha Bliss, and even “our cop” Chesley Sutherland – all of whom own their places in this story, too.

Beau and Glenda provided the body the rest moved within, but Haycraft Keebler was the heart in the heart in the heart of this city. Or, to keep with the metaphor of the place, draw the group as a windmill with Hay the hub, the rest reaching sails – because Haycraft was the history of the place; his family blood was. His ancestors had settled the land and built the house, saw it lose the farm-field vistas as the old drive was first scarfed by dirt road, then cobblestones, then pavement, up to the day in Haycraft’s adolescence when corruption charges were leveled against his legendary father. The family sold the house and fled to Tennessee.

The celebrated mayor of Montreux in wartime, renowned for his string ties and classical learning, his passion for the arts and the planting of dogwoods; the holder of a congressional seat, who had been awarded a bronze statue in Frederick Park for his dedication to the progress of his community – Haycraft’s father Edmund Keebler expired before his family in a splash of his own vomit. Perhaps for this reason Haycraft became the crusader he was, seriously disturbed if unaccountably charming. Our bipolar bear, the regulars called him.

Whether keeping with his lithium or not, whether coherent in his rhetorical oratorios or else slurred manic to the point of raving, Haycraft believed in the agency of a long-gone Old Towne community, believed it with feverish religiosity, refusing to acknowledge that community’s extinction, recognizing however its dormancy. This conviction had forced him through a life of perpetual crises and La Manchian quests, of plangent hours sired by doubt and solitude. Yet throughout all difficulties Hay knew he could transform the world.

And on this night, the night when this story starts, he shouldered his satchel beneath the windmill and through the double doors with ardent certainty that the first baby steps toward that transformation were now taken, enacted in the sabotage of a public bus.

Haycraft had his own philosophy, his own methods....